“It is better to have a classroom full of unanswered questions than unquestioned answers”. – Morgan, N. & Saxton, J. (1991). Teaching Questioning and Learning. New York: Routledge; 8.

What makes questions effective?

Effective questions produce thinking. Learning is the result of thinking. Therefore, questions are one of the most important tools used in teaching and learning. In this blog we will examine how both teachers can ask fewer and better questions leading to more time to think in class. We will explore routines that help students ask thoughtful questions to further their learning.

Effective questions generate in students thought and interest in making answers.

Effective questions are posed by both students and teachers throughout the learning process.

A good question:

- expresses genuine curiosity; behind every question there must be an intention to find out

- is a vehicle to clarify and make thinking visible

- is supported by tone and non-verbal signals that demonstrate interest

- engages our feelings as well as our thoughts

- challenges existing thinking and encourages reflection

- has reason, focus, and clarity

- is part of an on-going dialogue which involves relationships between speakers

- is paced so that listening to the answer is necessary

- results in an answer that creates change – either in the listener or in the next events

Loading…

Loading…

How do we know when questions are effective in furthering learning?

There are many important ways to think about the purpose of questions in the classroom. We often think of questions in terms of Bloom’s taxonomy. Teachers aim to ask more questions that encourage higher level thinking. We often judge the quality of a question by noting where the question falls on a range from concrete or the answer is “right there” questions to questions that inspire critical thinking or multiple debatable answers. The purpose of questions evaluated by Bloom’s Taxonomy is to inspire thinking. Therefore if the question asks for higher level thinking then the question is a better question. However, one might argue that “right there” questions are just as important as synthesis type questions. “Right there” questions may serve to confirm and clarify knowledge while synthesis type questions summarize. It might be impossible for students to synthesize if they have not clarified knowledge first; therefore both types of questions have value in learning. So, how do we know when questions further learning?

Rather than measuring the level of thinking in the question, it might be more useful to evaluate the quality of the question by the opportunity for answers. A high quality question can be evaluated by how the students formulate an answer to the question (alone, pairs, small groups and responses to think, talk, write, or draw) and what the teachers asks students to do with the answers to the questions. High quality questions result when the process used to answer a question matches intended purpose of the question. In addition to the process and purpose match, the amount of time devoted to answering a question may reveal more about the level of thinking required then the question itself.

In a completely different way, teachers use questions as a means to move the action in the classroom along, for example, “Does everyone have their notebook out?”, “Are we ready to go on?” Procedural questions help students to know the teacher’s expectations, for example, “What do we do after lunch?” “What should be included in your notebook?” These procedural type questions are essential and usually are in the greatest frequency of types of questions asked during a class period. It is important to note that students get in the habit of hearing questions that are part of a management dialog instead of a learning dialog. So, when the teacher switches to questions that demand thinking it is not surprising that many students do not recognize the change in expectations for answering questions.

There really isn’t such a thing as “good” questions and “bad” questions. But, there are questions that accomplish the teacher’s purpose. A communicated clear expectation for an answer is as important as the question. Students need to know when the teacher is using questions as part of classroom management and when the questions are part of learning. So, effective questions serve a particular purpose in a well developed classroom and are posed with an expectation of a specific type of thinking students will use in their response.

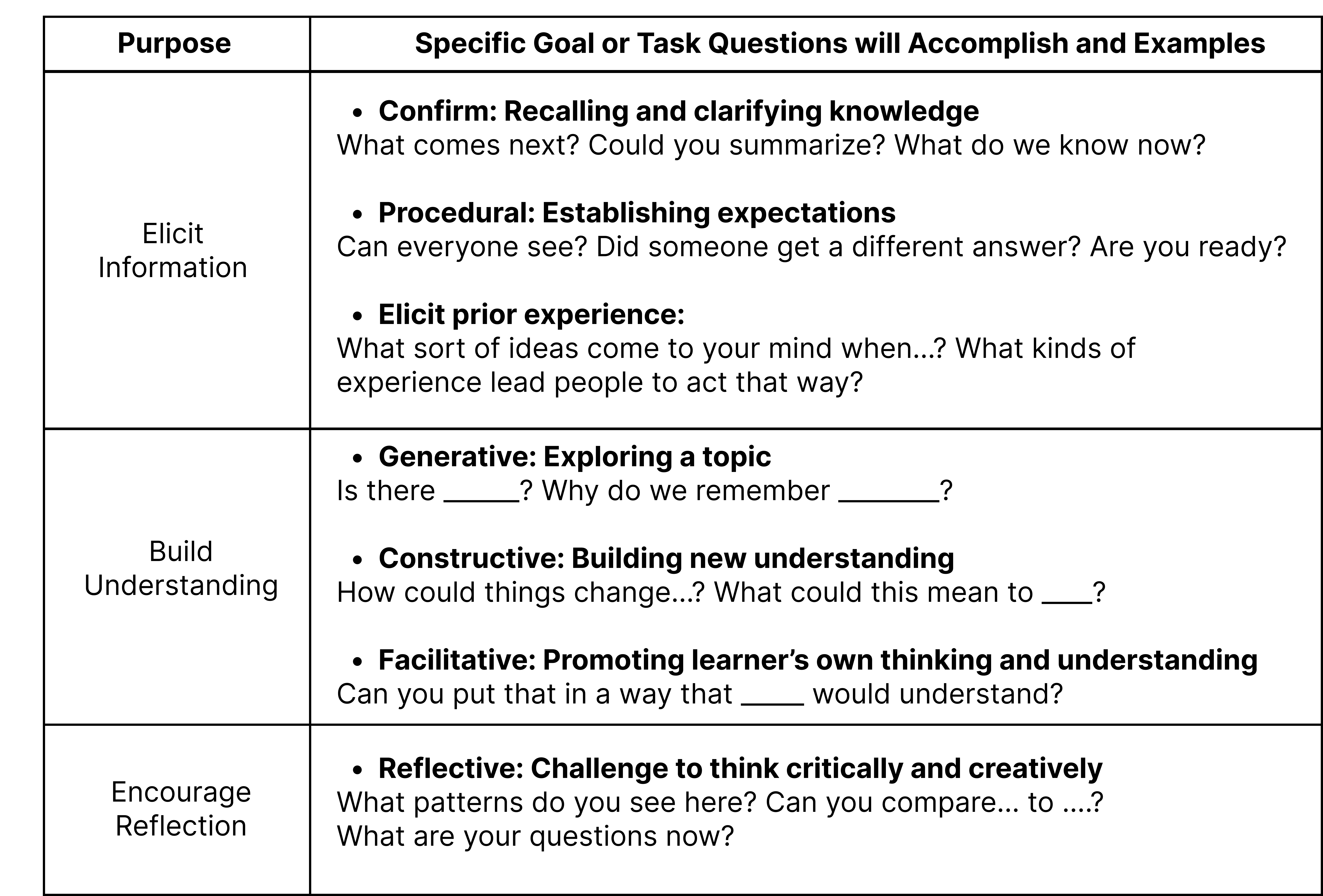

Classroom questions can usually be divided into three general purposes, to: elicit information, build understanding, and encourage reflection. Within each purpose questions can accomplish different goals or tasks. See the table below for examples.

Richhart, R. http://ronritchhart.com/Presentations_files/FIU_VT_Language%20%26%20Questioning.pdf

How do we ask Powerful Questions?

So now we have established the different purposes for asking questions in the classroom. But, how do teachers make questions powerful? How do teachers ask questions that efficiently and effectively move students in their thinking and understanding? How do questions help us build a classroom culture of collaboration and inquiry?

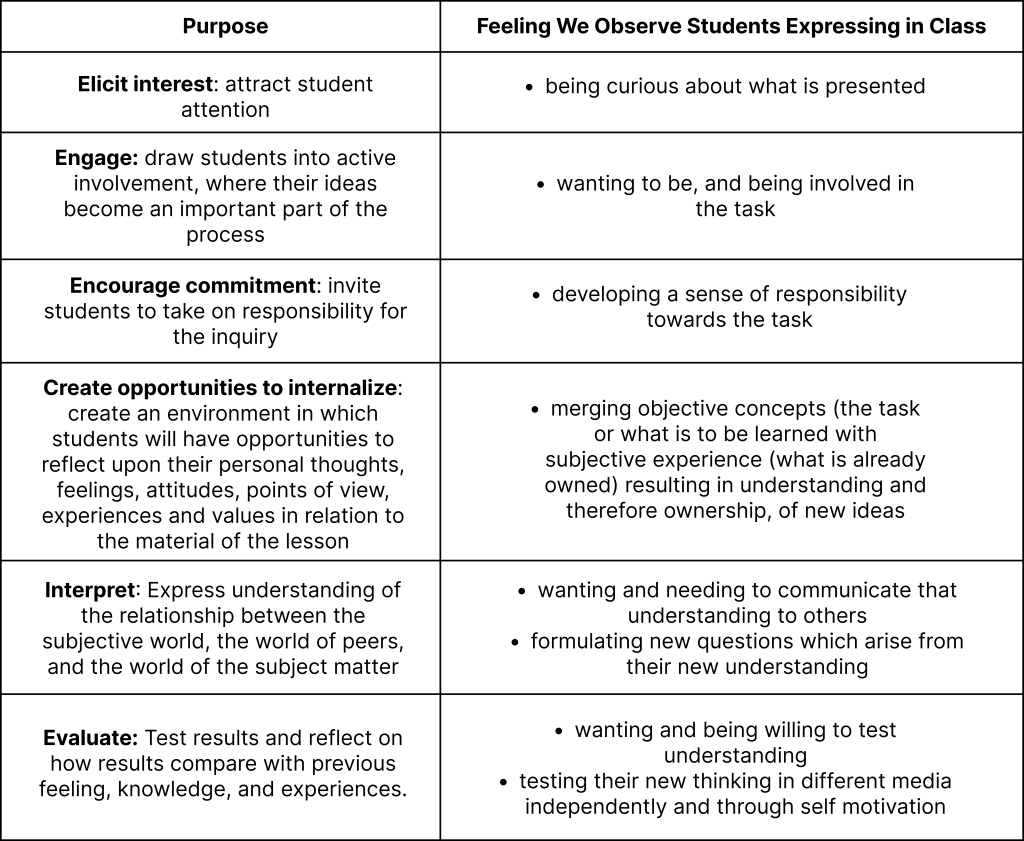

The Key #1 to Powerful Questions is Engagement: when we feel, think, and do at the same time

Powerful questions appeal to our feelings as well as our thinking and doing. Powerful questions invite and sustain student engagement in a learning experience. We cannot separate thinking from feeling and doing, so powerful questions connect to students on both an intellectual and a feeling level.

Powerful questions are the key to teaching for understanding. Students gain control over their learning when they see a relationship between what they are currently thinking, feeling, and doing with what they already know, feel, and have experienced. This sense of control over the learning helps students integrate new information with what they know to develop new understandings (Morgan, 21). Students cannot be given understanding by the teacher, rather students develop understanding by comparing their previous experiences with what they currently know, feel, and are experiencing. So, fostering engagement through questions is essential in developing student understanding.

There are different levels of involvement in every learning experience. Morgan and Saxton (1987) call this the Taxonomy of Personal Engagement. We can influence the type of engagement learners experience through the opportunities we create through questions and support students in building understanding.

Key #2: The expectation and process of achieving the answer is as important as the question.

- To what extent are you, as the teacher, like a student, seeking answers to questions?

Teacher Skills:

To be an effective questioner you will have to develop:

- The patience to wait for answers to be formulated,

- The skill of listening so that you will know how to respond,

- The finesse to ‘send the ball back’ in such a way that learning is perceived by your students as a dialogue in which everyone’s thoughts, feelings and actions are important elements for collective and individual understanding (Morgan & Saxton, 1987).

- Active listening, quality time to think and thoughtful answers (reflecting on one’s own answers).

Characteristics of active listening

- Genuinely interested in the reply and willing to let it change them in some way

- Are prepared to wait for answers

- Are as interested in others responses as they are in their own

- Are aware of the social context as well as the subject content

Characteristics of quality think time

- Everyone is comfortable with silence

- Is filled with the energy of curiosity balanced with thinking and feeling

- Interrupting silence is equal to interrupting a speaker

- Thought of as part of verbal expression and exchange

- Everyone knows what actions to take during think time, such as highlighting important notes, making connections, letting mind wander through thoughts, writing down ideas

Characteristics of thoughtful answers

- Can move the exploration on to a new stage

- Can raise the exploration to a higher intellectual and emotional level

- Shows respect for the question

- May not come easily; may be rephrased or hesitant

- Reveals level of thought and feeling of the responder

- Often appears in the form of a question

- Depends upon the care with which the question is put.

Key #3: Ask fewer, better questions, provide more time to think, and use the answers to further learning.

What do supports and extensions look like when asking questions?

“There can certainly be no change in understanding unless the question holds the possibility of an answer with personal meaning for the student. The more you know about students’ backgrounds, interests and experiences, the greater chance you have of choosing a question that holds that possibility.” (Morgan & Saxton, 1987, 24)

Teachers use their knowledge of student background, interests, and experiences to craft questions that both support and extend learner thinking. To assist students in both small and large group discussions, teachers use the Pocket Guide to Probing Questions or Naming Seven Types of Questions found in the resources section of this blog. Using examples of questions with clear purposes will lead to more thought provoking discussions in class and will help students form habits around asking purposeful questions to guide their own learning. Students will also be able to better determine what questions are asking on standardized tests.

Avoid asking simple questions as a way to support struggling learners.

Remember that interest lies in complexity. Our human brain is interested in things that are complex. So, a student may need to think concretely – but questions should have dimension and complexity. Offer supports such as visual aides including pictures, graphs or timelines to support students in answering complex questions. Important information for a question can be numbered or highlighted to offer supports for students who need their attention to be focused. Process supports such as sharing an answer with a partner or jotting down notes before answering to the whole group is another support. Another support is to provide questions on an index card for students to think about as a Do Now enables students to look up notes and prepare their answers before the discussion time in class. The key is to ask purposeful questions that demand thinking and answers that are useful to further learning of all students.

The art of questions involves active listening, thoughtful answers and time to think.

The key to good questioning is quality not quantity.

“The job of the teacher is to open doors; to let students know that doors exist, that there are many of them, that they are meant to be opened (some easily, some with difficulty) and that there is something beyond every door that is worthwhile knowing about. The key to the door, to carry the analogy further is, most often, the ‘good’ question. – Morgan, N. & Saxton, J. (1991). Teaching Questioning and Learning. New York: Routledge; 75.