“The principle goal of education is to create [people] who are capable of doing new things, not simply of repeating what other generations have done – [people] who are creative, inventive and discoverers” – Jean Piaget

Jerviw, K. & Tobier, A. Eds. (1988). Education for Democracy, Proceedings from the Cambridge School Conference on Progressive Education held at Teachers College, Columbia University, August 15, 16, 17, 1939. Weston, MA: Cambridge School.

What does teaching for understanding really look like?

When teachers and students come to school each day we intend to teach and learn for understanding. Certainly we are not working toward misunderstanding or confusion. Yet, how do we know if we are teaching for understanding? What does teaching for understanding look like in the classroom? Does teaching for understanding compete or interfere with teaching toward the learning standards? Is teaching for understanding just an elegant curriculum plan or is it day to day interaction among teachers, students, and the curriculum? These questions about teaching for understanding come up because understanding is not one obvious concrete visible object that can easily be seen and measured. In this blog we will explore teaching for understanding with the goal of clarifying what teaching for understanding looks like for teachers and students.

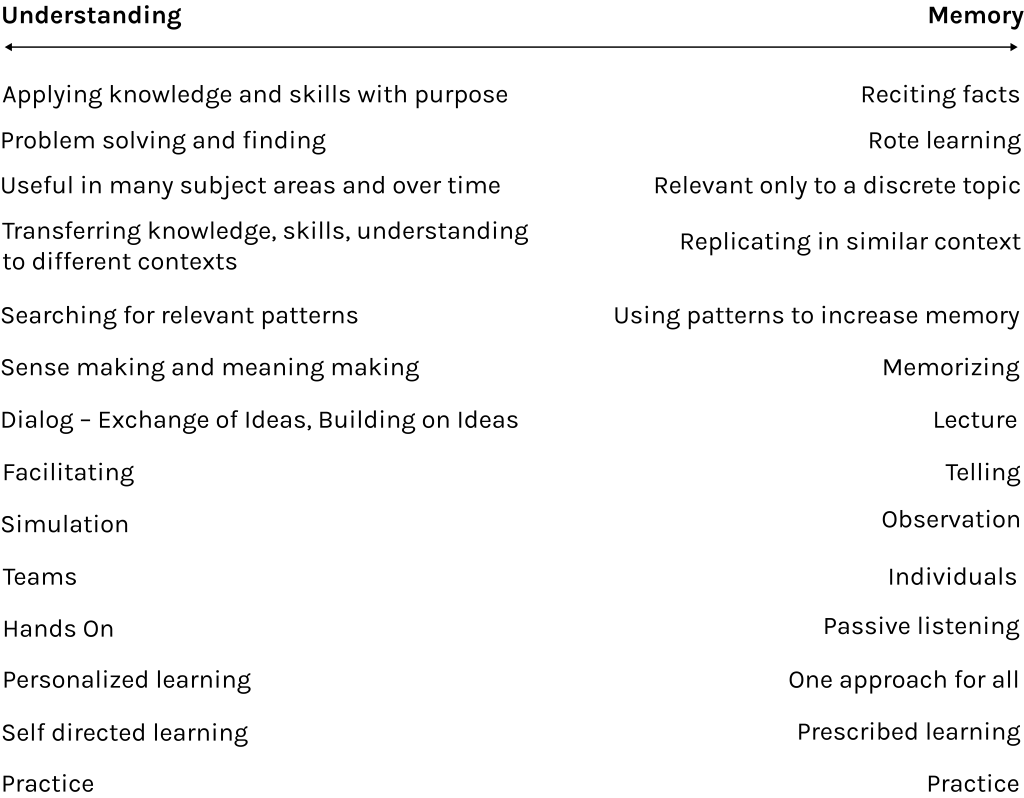

Piaget’s quote begins to define teaching for understanding by stating that a purpose of education is for students to develop the disposition to purposely and flexibly use their knowledge and skills. This is the goal of teaching for understanding, too. Teaching for understanding may be easier to see if we consider the differences between teaching for memory, where the goal is to replicate what is learned, and teaching for understanding, where the goal is to think flexibly with what is learned.

Let’s consider a US history class in high school. Once each quarter the teacher asks the students to define and describe with examples the American Dream. Students are expected to construct a short written response and may illustrate their thinking as well. The responses are posted on a bulletin board for all students to read and talk about. At the end of the second quarter the teacher asks students to define and describe with examples the American Dream again. Now, students are able to compare their responses to this big idea, The American Dream, from first quarter to second quarter. The teacher asks the students to point out evidence of their learning and experiences in the responses to determine to what extent students feel the learning in school affects their thinking and understanding of the American Dream. Students are asked to notice changes as well as consistencies in their thinking. At the end of third quarter students are ready for the familiar assignment. This time students make clear efforts to use their knowledge and skills to show their understanding of the American Dream. Again, students are asked to reflect on changes and consistencies in their thinking and understanding. This simple assignment related to a big idea is an example of teaching for understanding.

The American Dream assignment ensures that students are developing complex connections among the knowledge and skills they are acquiring through reading and class work over time. Students take time to reflect on their perspective, ways of thinking and understanding. The understanding goal is simple, “The American Dream” and the activity is completed in a period once each quarter. From this example, we can see that planning curriculum focused on developing understanding is practical. We can also see how students develop understanding over time by articulating their thinking and comparing previous thinking to current thoughts.

Let’s look at a pre-K class for another example. This class has decided to adopt a pet turtle. The teacher engages students in learning about turtles with essential unit questions such as: Are turtles smart? Do turtles communicate? How do turtles play? How could we find out if turtles like music? How are the parts of a turtle body made special for water? The class will be involved in many engaging activities such as reading both fiction and nonfiction books about turtles, completing observational drawings, caring for the turtles by researching the food, temperature, and space requirements, visiting a local aquarium to learn more, and studying the patterns on the turtles shell. Notice how the activities gain a much larger context and usefulness when conducted with the essential questions in mind. The essential question about how the body parts of turtles are special for water, requires the students to know the parts of the turtle body, but also requires students to use their knowledge to answer the question. This demand of purposefully and flexibly using the information we know is an important part of teaching for understanding. Throughout the unit the teacher reminds students of the understanding goal for the year, “How do patterns help us understand?” So, students will also seek patterns to help them understand more about turtles and the relationships among turtles, other animals, and the environment. The essential unit questions and the big idea of patterns are like a net for students to literally capture and connect the knowledge and skills about turtles. This net established in the minds of the children by the interaction of using knowledge to think through the essential questions and big idea will be useful beyond this turtle experience. As students acquire more knowledge about animals there is a fabric to store and path to retrieve information.

The process of learning for understanding is very different than learning for memory. This is not to say that there aren’t times when learning for memory is just what a student needs, for example, driving on the correct side of the road, knowing phone numbers, using locker combinations, or knowing the names of countries and states. However, the majority of time in a well developed classroom is planned to facilitate learners developing understandings. It is clear from the American Dream example and the Turtle unit that the activities that students engage in when pursuing understanding are very typical to most classrooms. However, the critical difference is that the students are involved in those activities through a larger purpose that will transfer to other subjects, situations, and activities. Teaching for understanding can take the same amount of time as teaching for memory. The difference is a clear understanding goal is used to guide student exploration, provide something for ideas to push against, add complexity to the topic, and weave connections to other topics and activities.

For example, examine the teaching for understanding versus memory on the chart below and envision different activities in your own classroom that illustrate the differences.

Why is this important?

Let’s use a metaphor that school is a grocery store where students come to gather all of the supplies (knowledge and skills) that they will need to make the things that they want and need in their life. If students go down the aisles and collect the knowledge and skills without a cart just trying to hold each individual item in their arms then soon they would start to drop things. Some items will get pushed back under their arms or become impossible to find. Understanding goals are like environmentally sound shopping carts or bags. They provide a structure where students can file knowledge and skills. This way the student can carry much more and there are connections between the items in the bags that help the student remember and find what they have learned to use in their life. If you think of a student moving through the day at school without any type of organizing bag or cart to file the collected knowledge and skills, then it becomes pretty clear why understanding goals are needed. It also becomes clear that when students use an understanding goal across subjects then more connections are built to the items in the bag. A greater number of connections will lead to remembering the knowledge and skills with greater ease as well as with more flexibility since each subject provides a different context.

What does Teaching for Understanding look like in a unit plan?

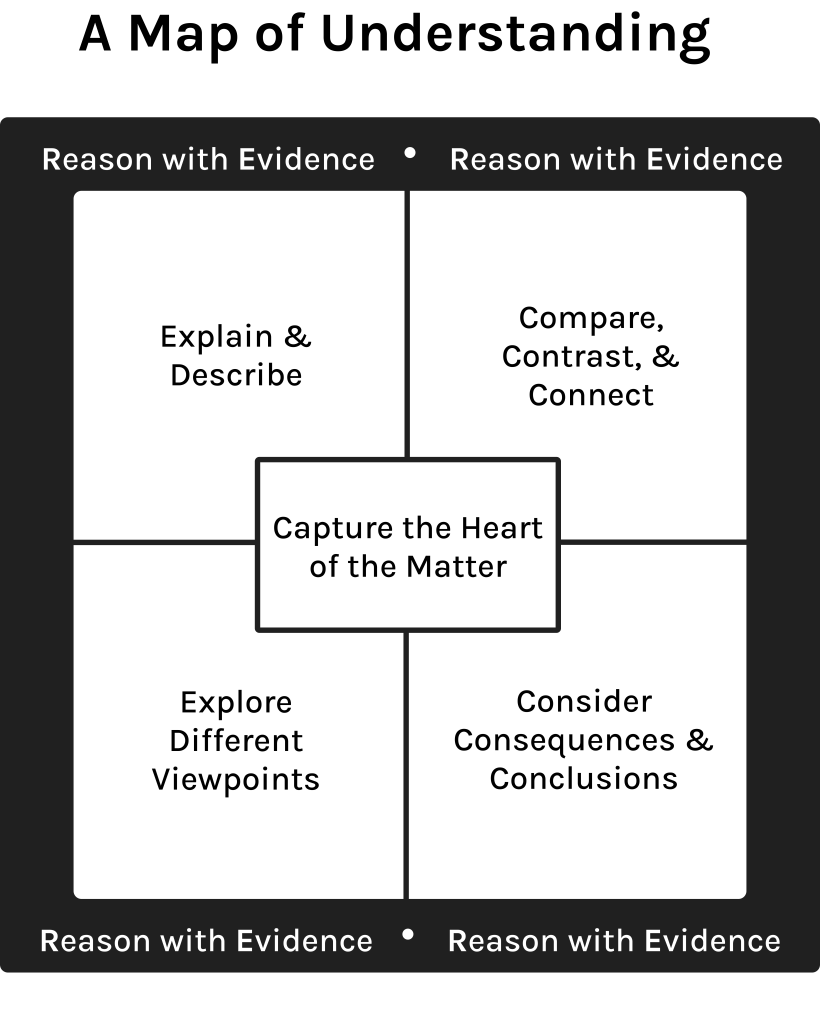

Understanding and thinking are elusive because the activity takes place inside our heads. The key to teaching for understanding is to plan activities that will make understanding visible for both the students and the teacher. One way to make understanding visible is to articulate clear understanding goals and to post the questions and goals. Then throughout the unit ask students to respond to the understanding goal and/or essential questions through a variety of activities so that student understanding becomes complex and visible to both the teacher and the students. Use the resource materials in this blog to develop understanding goals. The understanding goal will be a synthesis of the required standards. Use the chart below from Harvard’s Project Zero Classroom 2009 to develop tasks that make student understanding of a topic visible.

What does supports, extensions, and remediation look like when you are teaching for understanding?

Understanding goals are one of the few things in the classroom that is rarely differentiated. Typically all students are working toward a common understanding goal. Let’s think back to the turtle unit described earlier. Students may be reading books with varied levels of academic vocabulary, some students may be listening to books on tape, other students may be involved in interviewing the staff from the aquarium. But, all students will answer the question, “Are turtles smart? How do you know?” Usually, supports and extensions to ensure that all learners are both engaged and challenged happens to facilitate effective and efficient learning experiences. All students are engaged in wrestling with the same big ideas.

Connections

Quality Review Rubric

1.1 Design engaging, rigorous and coherent curricula, including the Arts, for a variety of learners and aligned to key State standards.

- c) Curricula and academic tasks are planned and refined using student work and data so that individual and groups of students, including the lowest and highest achieving students, special education students, and English Language Learners are challenged and engaged.

1.2 Develop teacher pedagogy from a coherent set of beliefs about how students learn best, and ensure that it is: aligned to the curriculum, engaging, and differentiated to enable all students to produce meaningful work products.

- a) Across classrooms teaching practices are aligned to the curriculum and reflect a coherent set of beliefs about how student learn best that is informed by discussions at the team and school level.

2.2 Align assessments to curriculum and analyze information on student learning outcomes to adjust instructional decisions at the team and classroom level.

2.2 a) Teams of teaches and individual teacher use or create assessments that offer a clear portrait of student mastery of the school’s chosen key standards and curricula providing meaningful and actionable feedback on the effectiveness of classroom level, curricular, and instructional decisions.

2.2 c) Teams of teachers and individual teachers develop expertise in selecting and/or designing assessments to gather and analyze classroom level data (e.g. student work, diagnostic assessments, projects) to supplement summative and Periodic Assessment data, create a picture of individual students’ strengths and areas of need, and differentiate instructional strategies.

3.2 Use collaborative and data informed processes to set measurable and differentiated learning goals** for student subgroups, and students in need of additional support

**Learning goals are defined by what students should know and be able to do embedded in curricula

3.2 a) Individual teachers and teacher teams use data to set annual and interim goals for groups of students for whom they are responsible (e.g. class, grade level, department, special needs students, English language learners)

3.2b) Individual teachers and teacher teams effectively and consistently analyze data to identify which students need additional supports and extensions, and set differentiated annual and interim learning goals for those students to accelerate their learning so all students are on a path to mastery of standards in the curriculum and fulfilling their potential

3.2 c) Team and classroom level goals have leveraged changes in classroom practice to accelerate student learning.

4.2 Engage in structured professional collaborations on teams using an inquiry approach**** that promotes shared leadership and focuses on improved student learning

****Inquiry approach is defined by the expectations of teacher teams in 4.2.b and across this rubric.

4.2 b) Teacher teams systematically analyze student assessment data, student work, and key elements of teacher work, resulting in adjustments to curriculum, instruction, assessments and resource allocation to improve learning outcomes for students they share or on whom they are focused.

5.2 Evaluate systems for assessing students, organizing data, and sharing information with student and families, making adjustments as needed to increase the coherence of policies and practices across the school.

5.2 a ) School leaders and faculty have structures in place to regularly evaluate and adjust assessment and grading practices, with a focus on building alignment and coherence between what students need to know and be able to do, what is taught, and how teachers assess what students have learned; school leadership and targeted teams have begun planning to integrate the expectations of the evolving state standards into assessment practices

More Resources

Printed Materials:

Blythe, Tina, and Associates. (1998). The Teaching for Understanding Guide. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hetland, Lois, and Veenema, Shirley (Eds.). (1999). The Project Zero Classroom: Views on Understanding. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Project Zero.

Perkins, D. (2009). Making Learning Whole: How seven Principles of Teaching can Transform Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Perkins, D. (1992). Smart Schools: Better Thinking and Learning for Every Child. New York: The Free Press.

RItchhart, R. (2002). Intellectual Character: What it is, Why it is Important, and How to Get It. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Veenema, Shirley, Hetland, Lois, and Chalfen, Karen (Eds.). (1997). The Project Zero. Classroom: New Approaches to Thinking and Understanding. Cambridge: Harvard Project Zero.

Wiske, Martha Stone (Ed.). (1998). Teaching for Understanding: Linking Research with Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Websites:

http://leamweb.harvard.edu/alps

ALPS, Active Learning Practice for Schools, is an electronic community dedicated to the improvement and advancement of educational instruction and practice. Its mission is to foster on-line collaboration between teachers / administrators from around the world and educational researchers, professors, and curriculum designers at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education and Project Zero.

Project Zero’s mission is to understand and enhance learning, thinking, and creativity in the arts, as well as humanistic and scientific disciplines, at the individual and institutional levels. PZ is an educational research group at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

http://wideworld.pz.harvard.edu

WIDE World (Wide-scale Interactive Development for Educators) is a relatively new distance learning initiative from the Harvard Graduate School of Education. It offers educators high-quality, coaching-based professional development at a distance, with a focus on teaching for understanding, thinking, assessment, and the integration of new technologies.