“The greatest sign of success for a teacher… is to be able to say, “The children are now working as if I did not exist.” – Maria Montessori

Why are Roles and Rounds important for Managing Small Group Work?

Managing small group work is one of the most challenging tasks for classroom teachers. Students learn best when they actively discuss ideas and work on tasks collaboratively. However, engaging all students in a learning activity and keeping all students on task is difficult when learners are dispersed among several small groups. Teachers often find themselves running from group to group to facilitate discussions, answer questions, and give directions. While the teacher is working with one group at a time, many students spend large amounts of learning time waiting for help from the teacher. Roles and Rounds are small group management patterns or routines designed to solve these classroom management issues to facilitate effective and efficient teaching and learning.

Loading…

Loading…

Students use the Roles or Rounds routine to complete an assigned learning task. Roles and Rounds help students learn skills such as taking turns, allowing everyone to participate, and dividing up tasks among group members. These skills are essential for working collaboratively and can be applied to every subject at all grade levels. Students efficiently complete learning tasks because the routine or learning process is known and has been practiced. Therefore students can focus on learning the new content because they know what to do in their group. Roles and Rounds enable teachers to monitor learning from a central location in the classroom, visiting groups strategically to move the learning forward instead of circulating to support the management of each group. Roles and Rounds enable teachers to achieve Maria Montessori’s indicator of success from the quote above, “the students are working as if the teacher was not there.”

What are Roles and Rounds?

Rounds

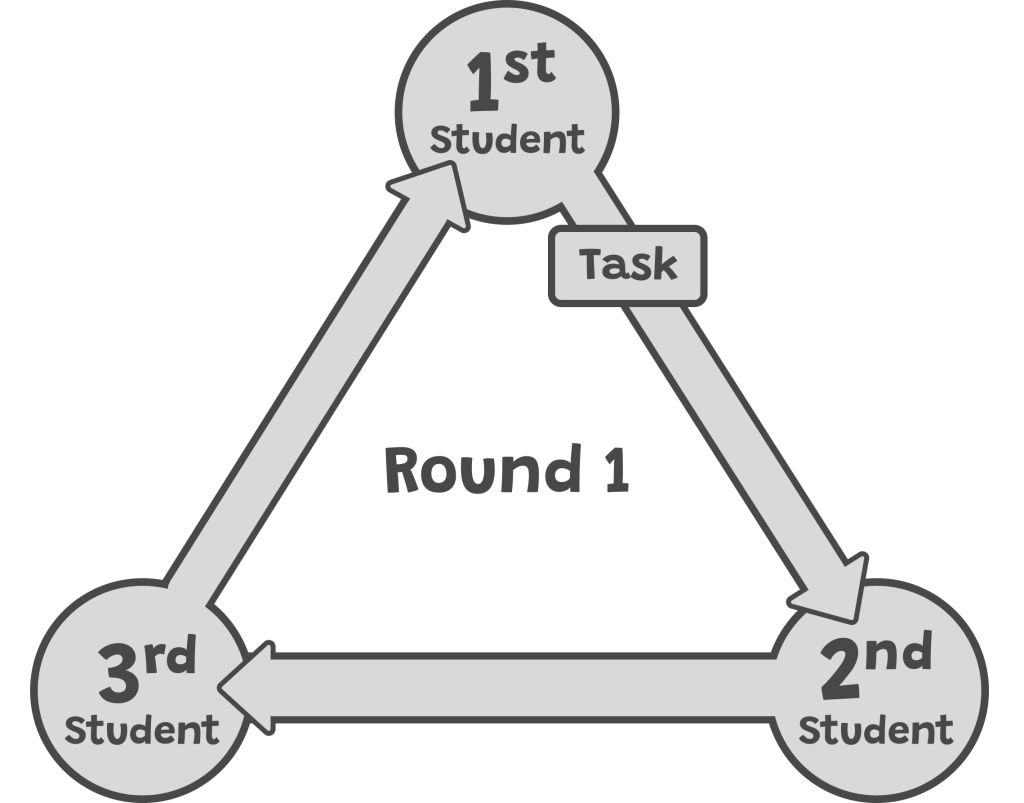

Rounds are when everyone in the group takes turns completing the same task around in a circle. For example, a group may use rounds to share a favorite part of the story, a reason that caused an event or to share an answer to a problem. Rounds ensure that everyone has a chance to talk and listen in a specified amount of time. Rounds can be repeated several times (for example, sharing answers may have ten rounds, one round for each problem) or the task can be changed for each round (for example, Round #1: Share the perspective of your opinion, Round #2: Share your opinion, Round #3: Share two reasons that support your opinion).

The purpose of rounds is to structure an opportunity for everyone in a group to share and listen. Rounds are especially useful in surfacing different perspectives and ensuring total participation.

Features of Rounds

- Every student does the same specific task.

- Each group member takes turns talking (or doing the task) in order around in a circle.

- Each round is usually timed by the teacher/facilitator.

- Learners can be in one large group or in several small groups.

Example: Homework Rounds

- Students correct homework in small groups by sharing their answers a round in a circle one problem at a time. If different answers come up then students discuss to figure out if a mistake was made or if there are multiple answers to the problem. A recorder jots down the number of problems that were discussed in the group on an index card. (Note: the teacher may be circulating or working specifically with one group or conferencing about homework with individual students during this time.)

- The teacher collects the index card from each group. Looking across the groups the teacher can easily see which problems many groups had trouble solving and different ways to adjust instruction to be more precise and efficient.

- Step Three: Instant Instructional Response might include:

- “go over” only the problems that most groups discussed

- Pull small strategy groups focused on the concepts in the problems that were discussed

- Review only the concepts that were discussed

- Add a few additional practice problems to review concepts that were discussed

- Create an exit card (2 to 3 problems including a question that asks students to explain their thinking) that requires students to use the concepts from the problems discussed to gain more information on individual student performance

Going over just the problems that confused many students and/or teaching a concept as well as meeting with small groups of students who made common mistakes is much more precise and requires more activity learning and reflection from students, and takes far less class time. Instant Instructional Response enables teachers to make precise decisions about how to structure class time and how to individually help students during a class period.

Roles

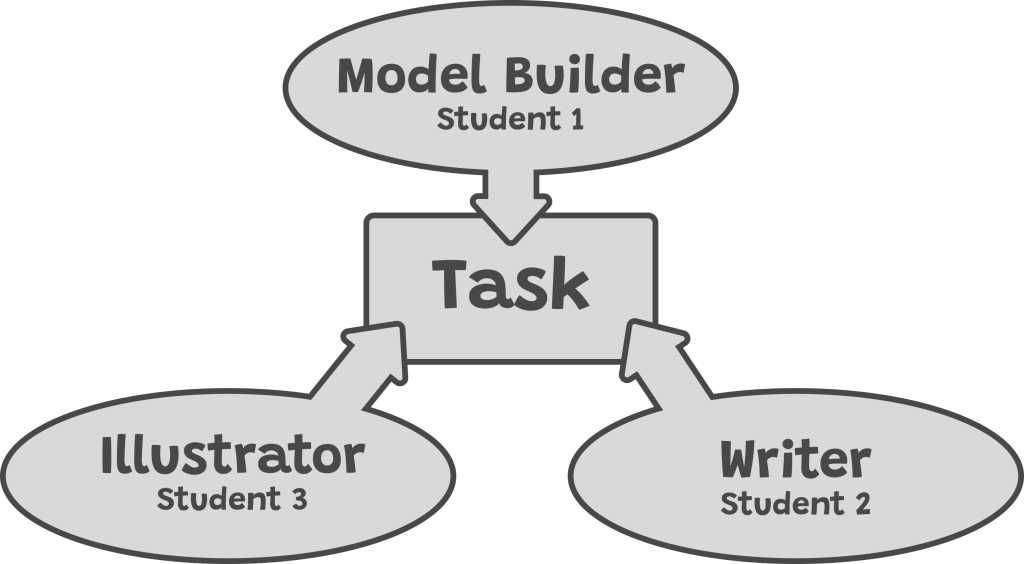

Roles happen when a group needs to divide a task into different parts to accomplish a goal. In an effort to be efficient, each person takes on a different task. Successful completion of the project depends on each task being completed.

The purpose of roles is to complete a task by dividing the work into different specific pieces accomplished by different people. Then the pieces are put together to complete the whole task. Roles are especially useful when the task is complex and when specific learner strengths, interests, or needs can be nurtured through a focused specific role.

Features of Roles

- Everyone in a group completes a different task related to accomplishing a specific role related to a goal.

- Roles can be used to divide complex tasks up into manageable pieces.

- Roles can be assigned to offer students opportunities to work and share their expertise in an area of strength or interest. Conversely, roles can be used to require learners to work in an area that needs developing.

- Roles can be used in combination with the jigsaw strategy where there are two groupings. In the first grouping, each group is assigned a different role and together the group accomplishes the task. Then the learners are regrouped into a second grouping so that each group has one person from each of the different roles. For example, if students are studying a country then the first grouping may have four groups researching different aspects such as people, land, economy, and government. Then in the second grouping would have one expert from each of the previous groups.

Example: Differentiated Problem Solving with Mixed Ability Groups

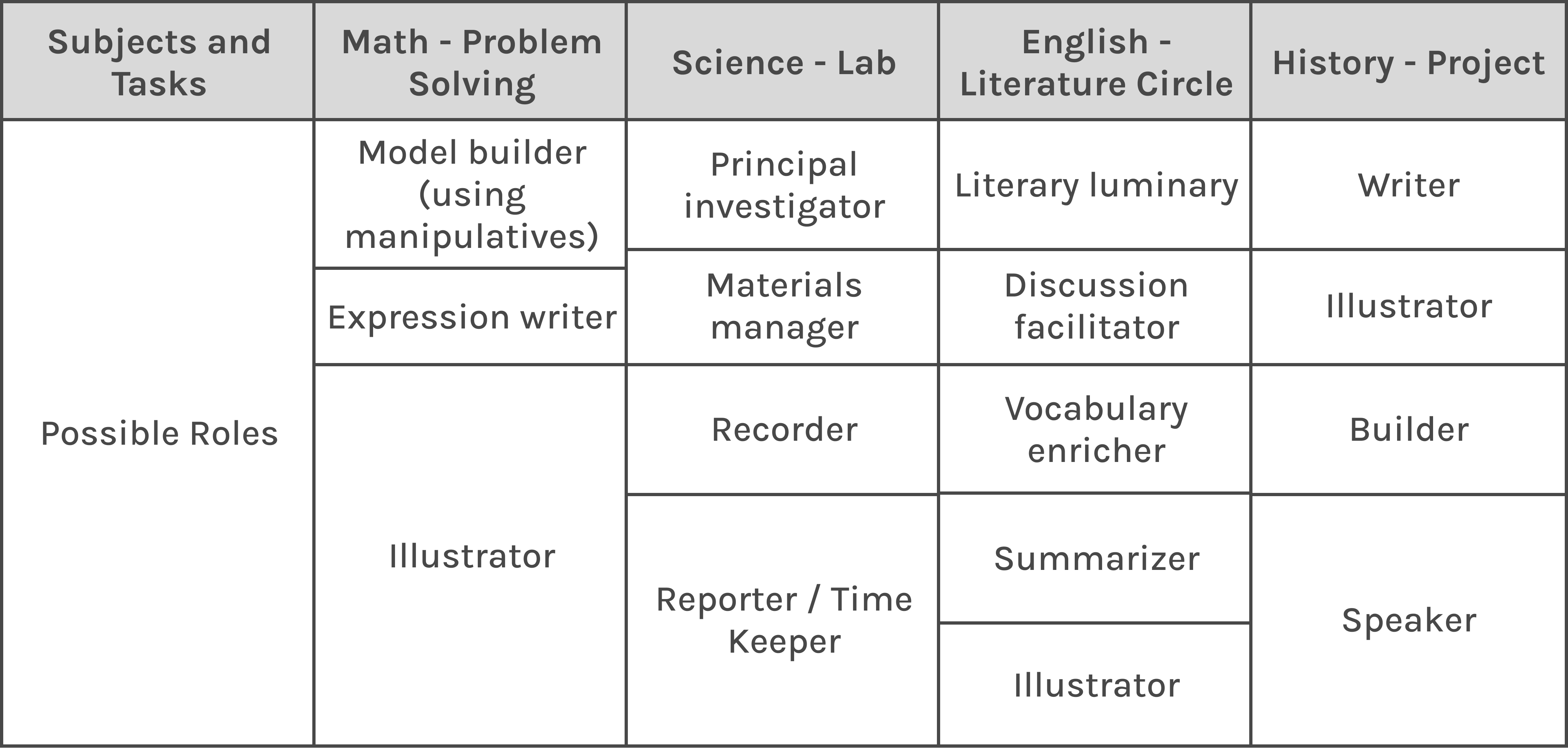

Students might be divided into groups of three with the roles, expression writer, model builder, and illustrator in a math class. The task is to solve the problems on a worksheet. The problems are organized in groups of three, the first problem being on grade level, the second problem having supports for learners who are struggling, and the third problem offers challenge for learners who have mastered the learning goals. Many math textbooks have practice problems organized in sections like this, so the teacher may not need to create problems for the worksheet.

To complete the worksheet, the teacher assigns the students to work in mixed ability groups. The students who are making expected progress are number one, students who are struggling with the concept are number two, and number three are students who are in need of greater challenge. By giving the students in each group a number, the teacher can assign the initial role and the order the students will rotate roles to match the level of difficulty of the problems on the worksheet. So, students who are number one in their group will be the expression writer and the first problem is on grade level, the number two student will be the model builder, and the number three student will be the illustrator. Then for the second problem the roles rotate. Now the student who is struggling will be the expression writer, the number three or more advanced student will be the model builder, and the number one student the illustrator. For example, supports in the second problem may include bold words to help students with vocabulary or may have more standard computation so that students can focus on setting up the equation.

The teacher determines the types of problems that would best support and extend the learners and then orders the problems on the worksheet so that students are positioned for the greatest engagement and rigor during group work. See the chart below for a possible rotation schedule. The key is to make sure that students are rotating in different roles and that the assigned problems are not all too hard or all too easy for the students.

How do I get started with Rounds?

To begin using using rounds, consider them as a whole class in a large circle, then dividing the class into halves with the teacher monitoring both circles from a central location, and then using rounds in small groups such as triads or four students.

- Teacher/facilitator explains what the task will be for each round. Often learners will complete a note card to prepare for the group work.

- Teacher/facilitator groups learners for a specific purpose. (For example, mixed ability, interest, reading completed, or topic of study)

- Learners from groups sitting knee to knee and eye to eye. (Do not allow students to sit in a line, wait for students to form groups where everyone can be seen and heard in the group)

- Learners decide or the teacher selects who will begin the rounds in each group.

- Learners or the teacher establishes which way in the circle the round will go and that only one person will speak going around in the circle. A round works like a row of dominoes falling.

- Learners know to stop when the round comes back to the person that began.

- Teacher/facilitator stands in a central location where he/she can hear each group and gives a signal to start round one.

- Teacher/facilitator can give the signal for each round or after groups are familiar with the process, learners may be able to move through rounds on their own.

- Learners have time to think about what they heard, considering patterns and surprises. Often learners add to their note card reflections of new ideas and questions generated by listen to others in their groups.

- Teacher/facilitator debriefs discussion with students focusing on what students learned in the rounds today and then on how the rounds went as a process and things to consider for the next time such as more time, smaller or different groups, and other suggestions to improve the experience.

Differentiating Instruction and Rounds – Using Supports and Extensions

- Groups can be formed based on specific learning needs or interests. For example, if some students need to review one topic and other students need to review a different topic then students could be grouped into two groups based on the topic that they need to review and then the actual rounds would be the same for all learners, however the topics for each circle would be different.

- Groups can have different tasks for the rounds based on student questions or needs. The groups need to function more independently if the tasks for the rounds are different among the groups.

How do I get started with Roles?

Introduce “roles” with students by starting with a task to be completed with a partner. For example, recorder and presenter, note taker and summarizer, help seeker and reporter, vocabulary researcher and a literary element identifier, problem solver and problem checker. Usually when partners are assigned roles they complete their task and then change roles so that each partner does both roles. Then roles can build up to three, four, and larger groups of students forming teams with specific positions.

- When a task is to be completed by small groups then the teacher considers whether roles or rounds or a combination of the two strategies will be most effective and efficient in terms of learning.

- If roles make sense for instruction then the teacher articulates, the roles, tasks, criteria for completing the tasks, and gathers/makes instructional materials.

- Learners are either assigned or on occasion select the role that they will accomplish. Often roles rotate with each problem, question, or with each experiment or discussion so that everyone completes each role.

- Learners can accomplish their role with other learners from other groups who are working in the same role and then join their group with the task completed ready to share. Or students might accomplish their role as homework and then collaborate during class with group members in different roles. Sometimes students simply do their role when their turn comes up in the small group work.

- Once all of the roles are shared the group puts together the pieces to accomplish the task.

- It is useful for learners to share their work from their role with the group in a “round” format. It is useful for group members to hear questions and feedback on their work in a “round” format as well.

Differentiating Instruction and Rounds – Using Supports and Extensions

- Roles should be developed and assigned based on instructional goals.

- The content materials different roles tackle can vary based on reading level or many other academic readiness levels or on learner interest.

Where to begin: Planning to Use Roles and Rounds

It is useful to plan for Roles and Rounds with grade level teams or department teams. If every teacher on a grade level team is using “rounds”, but in different ways, then students will know the routine and can focus on the curriculum that they are learning. So, there are advantages to common small group management routines across departments and grade levels. Here is an exercise to begin developing Roles and Rounds.

Rounds

- Think of the first week of school or the first week of a unit or quarter and the activities that need to be accomplished.

- Identify at least one task that can be accomplished through rounds.

- Share with a colleague your idea for using rounds and why rounds will be particularly useful and efficient for accomplishing this task with learners.

Roles

Option #1

- Make a list of tasks that students complete in a particular unit or course that have specific parts that require a special skill or knowledge to complete.

- Identify the roles that would make each part more efficient and effective for learners if they could focus on the part separately and on using the needed skill.

- Share with a colleague your idea for using roles and why roles will be particularly useful and efficient for accomplishing this task with learners.

Option #2

- Consider projects and tasks that are accomplished in partner, triads, or small groups during the school year (use a curriculum map to identify the projects/tasks).

- Identify at least one project or task where roles would be both efficient and effective.

- Share with a colleague your idea for using roles and why roles will be particularly useful and efficient for accomplishing this task with learners.

- Think about how roles and rounds might be used together.

Launching Roles and Rounds

Think about how roles and rounds will be established as a routine in your classroom.

Students will need to understand that:

- Group conversations and projects can be managed by “rounds and/or roles” and students can organize and implement “roles and/or rounds” independently of the teacher.

- Participation in small groups includes knowing the learning purpose or goal of talking and listening to each other and using a procedure to ensure that everyone has the opportunity to participate.

- Clear expectations and norms for participation in small group conversations, including physically how to sit so that everyone can be seen and heard must be established and maintained by the group members (for example, sitting knee to knee and eye to eye and politely confronting someone who is not participating or participating too much).

More Resources for Supporting Student-led Small Group Conversations

Brashears, D. & Krull, S. (1981). Circle Time Activities for Young Children. Mt. Rainier, MD: DMC Publications.

Daniels, H. (1994). Literature Circles: Voice and Choice in the Student-Centered Classroom. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publisher.

Daniels, H., & Harvey, S. (2009). Comprehension and Collaboration: Inquiry Circles in Action. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

McDonald, J., Mohr, N., Dicther, A., McDonald. (2007). The Power of Protocols: an Educator’s Guide to Better Practice. 2nd Ed. New York: Teacher College Press.

National School Reform Faculty (NSRF Materials) http://www.nsrfharmony.org/protocol/protocols.html

O’Connor, C., Anderson, N., Chapin, S. (2003). Classroom Discussions: Using Math Talk to Help Student Learn, Grades 1-6. Sausalito, CA: Math Solutions Publications.

Smithenry, D. & Gallagher-Bolos, J. (2009). Whole-Class Inquiry: Creating Student-Centered Science Communities. Arlington, VA: National Science Teachers Association.

Swarta, L., Nyman, D., Booth, D. (2010). Drama Schemes, Themes & Dreams: How to Plan, Structure, and Assess Classroom Events That Engage All Learners. Markham, ON: Pembroke.

Visible Thinking Routines, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Project Zero

http://www.pz.harvard.edu/vt/VisibleThinking_html_files/03_ThinkingRoutines/03a_ThinkingRoutines.html (Note: These routines work well for small groups and fit well with the structure of Roles or Rounds).