“Great minds have purposes, others have wishes.” – Washington Irving

How do we communicate clear learning goals to students?

The plethora of terms that describe learning goals often create more confusion than clarity in helping teachers map out curriculum and communicate clear expectations to students. Washington Irving’s quote emphasizes the relationship between “great minds” and clear “purposes”. In this blog, we will explore the meaning of learning goals and the use of eight terms: standards, Common Core Standards, learning targets, lesson objectives, SMART goals, essential questions, enduring understanding, and depth of knowledge to establish clear purposes and expectations with students.

We see terms like learning goals, learning targets, essential questions, and lesson objectives, but what do all of these terms mean? Can these terms be used to help students learn? Let’s begin by defining learning goals, a term found in many documents, including the Quality Review Indicator 3.2.

Definition

Learning goals identify the intended achievement, a desired change in understanding, knowledge, and/or skills. The change in understanding, knowledge, and/or skills may take place through acquiring new, revising existing, and/or using different applications. The intended achievement takes place through a learning experience. Learning experiences may include: activities (informal/formal), lessons, courses, series of courses, programs, and other opportunities.

Where to begin?

Standards establish basis of the curriculum defining the intended achievement; therefore learning goals begin with standards. Standards are divided up into units of study that enable students to progress to mastery over time. Standards are often too large or written in language that is difficult to use in the classroom. Therefore, teachers create Learning Targets based on the Standards for use with students. The Learning targets are used throughout teaching and assessment activities to help students monitor and pursue mastery of the standards.

Learning goals identify the intended achievement by describing what students will be able to know and do within the established curriculum (Quality Review, Indicator 3.1). In addition to standards, the curriculum includes building conceptual relationships among the standards and key ideas of the subject area. So, learning goals also include enduring understandings and essential questions that make visible to learners the larger context of the subject area from where the standards originated. The intended achievement is made visible through assessments that measure changes in understanding, knowledge, and/or skills. The intended achievement is realized through organized learning experiences guided by lesson objectives. Lesson objectives and learning targets have in common that they are most effective when they are SMART (specific, measurable, agreed upon, relevant, and time-based). So, we begin to see how many terms are used to define learning goals and chart roads leading to the intended achievement.

It may be useful to think of learning goals as a road map and the many terms used with learning goals as the elements and destinations on a road map. The road map both directs and records the journey of learning, making visible the intended achievement along with the different routes and landmark achievements along the way.

If a curriculum map is like a road map then standards are the roads on a map. Standards can be major roads that are traveled with great frequency and result in access to many places. Other standards or roads are less vital, although necessary to arrive at certain locations. When we look at a curriculum map we can see the standards that serve as the major roads receiving more time and priority over standards that lead to places that are used less frequently.

Learning targets are the push pins locating the specific places that we plan to visit. The push pins are important because we feel a sense of accomplishment when we arrive there. We often take pictures or make an effort to record ourselves in this place in the way that students might be asked to save a piece of work or take a test to remember their mastery of this place on the map. Learning Target-push pins give travelers a purpose for the journey. The push pins are particularly good models to represent Learning Targets because push pins are small and movable, yet visible to everyone. Learners can travel down different roads heading toward the same push pin. We often see the same learning target or push pin appearing in more than one location on a curriculum map or on maps from different subject areas. Learning targets are rooted in standards, just as the push pins are secured into the roads.

Learning goals (standards, learning targets, essential questions, enduring understandings, and lesson objectives) are particularly useful in the context of a curriculum map where they are placed within a larger landscape of the subject area. Thinking of learning goals as elements on a road map is very practical because the amount of time needed to arrive at a destination, difficulty level of travel, and length of the roads are variables that we use in teaching plans, too.

Let’s begin by defining and connecting eight terms that enable us to describe learning goals:

1

Standards – The structures that define the curriculum map, connected to everything on the map.

Standards are a clear definition of what knowledge and skills will be taught and what students will do to demonstrate mastery. Ravitch, D. (1995). National Standards in American Education: A Citizen’s Guide. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution (25). New York State Learning Standards and core curriculum guidance documents are the foundation upon which State assessments are developed and aligned. Find the NY State standards and link to the Common Core State Standards http://www.p12.nysed.gov/ciai/cores.html.

2

Common Core State Standards – The new standards used by 48 states, the structures that define the curriculum map, connected to everything on the map.

Common Core Standards define the rigorous skills and knowledge in English Language Arts and Mathematics that need to be effectively taught and learned for students to be ready to succeed academically in credit-bearing, college-entry courses and in workforce training programs. The initiative was a state-led effort coordinated by the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) and the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). The standards were developed in collaboration with teachers, school administrators, and experts, to provide a clear and consistent framework to prepare our children for college and the workforce. Learn more at http://www.corestandards.org/ .

“On July 19th, 2010, the New York State Board of Regents adopted the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) for Mathematics and CCSS for English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects, with the understanding that New York State may add additional expectations to the Common Core.” http://www.p12.nysed.gov/ciai/common_core_standards/

3

Learning Targets– Push pin planned destinations, based on Standards.

Learning targets are statements of intended learning based on the standards. Learning targets are written in language for student use. Learning targets are matched to assessments that will make visible student mastery of the learning target. Students use learning targets to guide their own learning. Learning targets appear on performance summaries at the end of homework, tests, and projects. Learning targets appear on rubrics enabling students to give themselves feedback toward next steps in mastery of learning targets. In short learning targets appear on all instructional materials used in a unit.

4

Lesson Objectives – The itinerary for the learning trip, designates how much time, the route, expected number of travelers, and the products of each day of travel. The itinerary lists both the travel goals – push pin learning targets and the roads or standards that will be traveled.

Lesson objectives generally refer to the tangible outcome at the end of a lesson. Lesson objectives are usually phased in behavioral terms such as:

“Students will be able to (1) with (2) accuracy through the (3).”

Lesson objectives clarify:

- What students will accomplish during this lesson

- To what specific level (i.e. 75% accuracy) the students will perform a given task in order for the lesson to be considered satisfactorily accomplished

- Exactly how the students will show that they understood and learned the goals of your lesson, for example, through a worksheet, group work, presentation, or illustration.

5

SMART Goals – The criteria used to articulate clear Learning Targets.

SMART is a mnemonic used to remember the criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of goals. The SMART criteria – specific, measurable, agreed upon, realistic and time-based can be used to develop high quality learning targets. See more ideas below of terms that may help to strengthen the specificity of learning targets.

S – specific, significant, stretching

M – measurable, meaningful, motivational

A – agreed upon, attainable, achievable, acceptable, action-oriented

R – realistic, relevant, reasonable, rewarding, results-oriented

T – timely, time-based, tangible, trackable

Gagne, R., Briggs, L., Wager, W. Principles of Instructional Design, Third Ed. New York: Holt, Reinhart and Winston: 1988. Read more at Suite101: Creating Classroom Lesson Objectives That are SMART

6

Essential Questions – Synthesize standards and represent core ideas of a discipline, connect to Learning Targets and are frequently used in Lesson Plans and Assessments.

Essential questions are provocative questions that point to key inquires and core ideas of a discipline. There are multiple answers to essential questions and the questions are relevant to over time (throughout a year long course and often in a subject area over many years). Essential questions guide students in exploring enduring understandings. Examples might be: “Is progress good?”, “Is less really more?”, “What food is sustainable?”, “Does color have energy?”, “How do we know something is old?”, or “Are heroes also villains?” Through mastery of learning targets students are able to answer, reflect on, and revise their answers to essential questions.

7

Enduring Understanding – Is the compass used to explore the map, the compass provide direction, but can change with different perspectives.

Enduring understandings are big ideas that have lasting value beyond the classroom, capture the heart of the discipline, and engage learners in exploration and revision of thinking. When students answer an essential question they are developing an enduring understanding. Students often look for patterns among answers to essential questions as well as answers from different perspectives as a means of building enduring understandings. Sometimes teachers use one enduring understanding as a throughline that connects all units in a course/curriculum. Enduring understandings can be phrased as statements, questions, or a single word. Some examples include: “Models build understanding.”, “Relationships explain everything.”, “What is beauty?”, “What is communication?”, “Patterns”, “Cooperation”, or “Perspectives”. Enduring understandings are used from elementary school through high school and are relevant to more than one subject area. For example, “How can we measure change?” might be used in an elementary science class studying the seasons, in a middle school English class working on the writing process from drafts to final edits, and a high school science class studying the age of the universe or a high school class considering the results of laws. Students develop enduring understandings over many years of study and through different disciplines.

8

Depth of Knowledge – Scale that helps align the cognitive demands of the standards and assessments.

The Depth-of-knowledge (DOK) was created by Norman Webb from the Wisconsin Center for Education Research (1997). The DOK levels help determine the match between how deeply students would have to know the content to give a response to an assessment. A full range of cognitive complexity may be measured for each standard. The Levels of DOK are Level 1: Recall, Level 2: Basic Application of Skills/Knowledge, Level 3: Strategic Thinking, Level 4: Extended Thinking. The level of DOK is determined not be the verb associated with learner actions in the assessment alone. Both the verb describing the task along with the content needed to respond in the assessment determines the level of cognitive demand. Depth of Knowledge, one of six dimensions, were issued by the U.S. Department of Education as important factors in making judgments about the alignment between state standards and assessments. These dimensions include comprehensiveness, content and performance match, emphasis, consistency with achievement standards, and clarity for users as well as Depth of Knowledge (1999).

Why are all of these terms important?

“to use assessment productively to help achieve maximum student success, certain conditions need to be satisfied. Our achievement targets need to be clear. State standards need to be deconstructed into curriculum maps that are articulated within and across grade levels, and the resulting classroom- level achievement targets must be translated into student- and family- friendly versions.”

Rick Stiggins, From Formative Assessment to Assessment FOR Learning: A Path to Success in Standards-Based Schools, Phi Delta Kappan, Vol. 87, No. 04, December 2005, pp. 324-328. http://www.assessmentinst.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/05/fromformat_k0512sti1.pdf

Standards and learning targets aligned to assessments are the keys to effective teaching and learning. Curriculum maps articulate a sequence of units established by standards and learning targets that are aligned with assessments. These maps not only define the goals, purposes, and structures for learning, but also enable learners and teachers to see accomplishments along the journey of learning.

What does this look like?

Curriculum maps are the first place teachers put all of these terms into action. Key elements include standards and learning targets matched to assessments. The sequence of units shows progression of skills over time and priorities by the amount of time scheduled. Learning goals standards, learning targets, essential questions, and enduring understandings. While standards and learning targets articulate what student will know and be able to do. Enduring understandings and essential questions are used to develop complex ideas and articulate throughlines of a course and subject. The enduring understandings and essential questions like standards and learning targets are all matched to the assessment that will measure student progress toward mastery of that goal. Goals are matched to assessments when students receive specific feedback on progress toward that measure.

The most important part of the curriculum map is the relationship among the elements. Key relationships to examine in a curriculum map are:

- The match of goals to assessments

- Patterns of practice and progression of skills/knowledge over time

- The amount of time planned for the goals and assessments

The curriculum map is the first step in articulating the clear goals and purposes where great minds thrive. Let’s take a look at a template for a curriculum map and a few completed map examples:

What terms are shared with students?

After the curriculum is planned, the next step is sharing the learning goals with students. Don’t let curriculum maps be an artifacts in a notebook in an office. Keep curriculum maps in lesson plan books or posted in the classroom. Students as well as teachers can use curriculum maps to monitor their own progress.

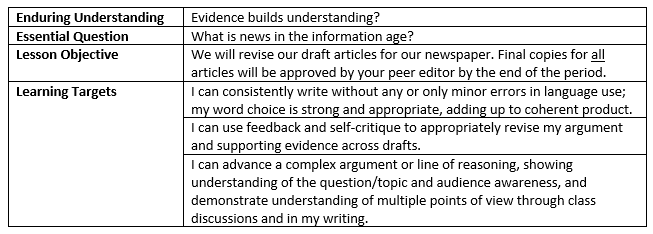

The posted agenda for a Humanities class might look like this:

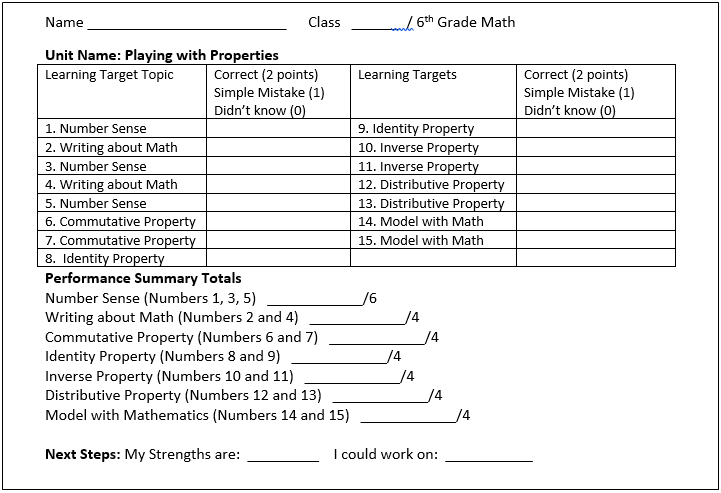

A performance summary at the end of a middle school math test might look like this:

Learning Goals: Guiding Learning, Leading to Achievement

While setting clear learning goals for students has been shown through research to have a positive impact on student achievement (Marzano, R. (2007). A Handbook for the Art and Science of Teaching. Alexandria, VA: Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development), the goals can come in different grain sizes. There is teacher, team, and school autonomy in determining how learning goals are created, communicated to students and parents, and tracked. The frequency and number of learning goals are also aspects that cannot be prescribed so that they are effectively used.

This said, the intended achievement described through learning goals is defined by what students will be able to know and do within the established curriculum (Quality Review, Indicator 3.1). Learning goals should describe the intended achievement, a desired change in understanding, knowledge, and/or skills. As a result, learning goals begin with established standards and lead to learning targets needed to master the standard. The intended achievement is measured through assessments that accurately reflect changes in student understanding, knowledge, and skills. Feedback to students is explicitly connected to the steps students must take to meet the learning targets, mastering the standards and building enduring understandings, ultimately achieving the learning goals.

The intended achievement is accomplished through organized learning experiences which are guided by lesson objectives. And while every goal doesn’t have to be “SMART”, lesson objectives and learning targets become more clear, and the demonstration of learning by students more apparent, when learning goals specific, measurable (qualitatively as well as quantitatively), agreed upon, relevant, and time-based.

For more on student learning goals, and some specific examples, see the Quality Review memo from the fall of 2009.

More Resources

Common Core Standards http://www.corestandards.org/

New York State Standards http://www.p12.nysed.gov/ciai/cores.html

New York State Assessments http://www.p12.nysed.gov/osa/

Stiggins, R. (2007) Assessment through the Student’s Eyes. Educational Leadership. Alexandria, VA: Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Webb, Norman L. and others. “Web Alignment Tool” 24 July 2005. Wisconsin Center of Educational Research. University of Wisconsin-Madison. 2 Feb. 2006. http://www.dese.mo.gov/divimprove/sia/msip/DOK_Chart.pdf

Wiggins, G. and J. McTighe. (1998). Understanding by Design. Alexandria, VA: Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

Wiggins, G. and J. McTighe. (May 2008). Putting Understanding Up First. Educational Leadership. Alexandria, VA: Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD). 65:8: 36-41